Prishtina, 26 November 2025

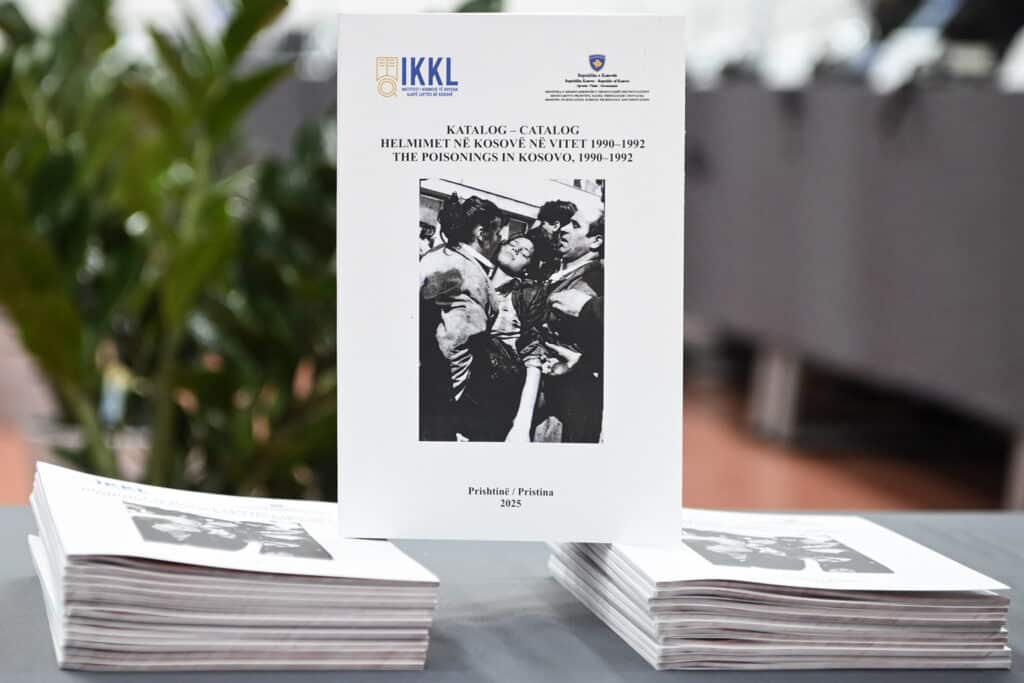

The Acting Prime Minister of the Republic of Kosovo, Albin Kurti, participated in the second edition of the “Zá n’Kujtesë” Forum, which this year was dedicated to the poisoning of students in Kosovo during 1990–1992. This new edition, organized by the Institute for the Research of Crimes Committed During the War in Kosovo in cooperation with the Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Innovation, brings forward documents, photographs, and testimonies from the time, illuminating one of the darkest episodes of the 1990s.

In his opening remarks, Prime Minister Kurti said that he was pleased that six months after the first “Zá n’Kujtesë” Forum, which focused on Albanian soldiers killed during their service in the Yugoslav army, today they have gathered for the second forum, which addresses the poisoning of students in Kosovo in the early 1990s.

“Among all the crimes committed by the occupying state of Serbia against Albanians in Kosovo, one of the most gruesome and diabolical crimes was precisely the poisoning of students. Many of us here lived through that dark time, which in my own memory remains vivid even today, as I was a first-year student at the ‘Xhevdet Doda’ Gymnasium in Prishtina when, in the spring of 1990, it became clear that students were being poisoned in schools,” said Prime Minister Kurti.

In his address, he recalled the period when the poisonings began in Kosovo—on 21 March 1989 in Klina and on 6 December 1989 in Prizren—stating that while preparations were underway for the abrogation of Kosovo’s autonomy, which occurred on 23 March 1989, only two days earlier the first cases of poisoning were recorded at the “Luigj Gurakuqi” school in Klina. In the months that followed, beginning on 15 March 1990, cases of poisoning would be recorded in 20 towns and 11 villages across Kosovo. Beyond schoolchildren, cases of poisoning would also be registered among workers at the “Emin Duraku” textile factory in Gjakova, the “Ballkan” factory in Suhareka, the “Polet” factory in Vushtrri, and sporadically among passers-by. It was even reported that seven children had been poisoned in the “Emin Duraku” nursery in Gjakova. On 19 March 1990, there were mass poisonings of Albanian students in Podujeva, followed by another wave on 22 March. The peak day of poisonings was 20 March 1990, when cases of poisoned students were reported in numerous towns across Kosovo. The highest number of affected students was recorded in the municipality of Ferizaj, whereas over the years, it has been estimated that the total number of poisoned students reached 7,421.

“The Serbian authorities attempted to camouflage these poisoning cases by obstructing investigations and medical analyses. They also persecuted those involved in providing assistance, such as the 48 students of the Faculty of Medicine who were imprisoned for what was described as the unauthorized provision of medical assistance. Despite these efforts, these state crimes committed by Serbia have undoubtedly left behind extensive evidence,” the Prime Minister said.

Alongside the testimonies of the victims themselves, the witnesses, various medical reports, and reports by international organizations and political figures of the time, the Prime Minister underscored the importance of documenting the crimes committed by Serbia in Kosovo through the institutions of the state of Kosovo. It is precisely with the aim of collecting every material and every piece of evidence on all crimes of any period committed by Serbia against Albanians and others in Kosovo that the Institute for the Research of Crimes Committed During the War in Kosovo was established. Within this Institute, an archival, library, and audiovisual center is being created to serve researchers, journalists, jurists, and policymakers interested in the historical truth of Kosovo and in the policies related to addressing it, the Prime Minister added.

“By collecting evidence of the poisonings and all crimes committed by the Serbian state in Kosovo, by safeguarding these truths through our state institutions and cultivating collective memory as a society—by knowing and remembering—we ensure that fascism is not allowed to return and that the past does not repeat itself,” he said in conclusion.

Prime Minister Kurti’s full speech:

Honourable President of the Republic of Kosovo, Ms. Vjosa Osmani Sadriu,

Honourable Director of the Institute for the Research of Crimes Committed During the War in Kosovo, Mr. Atdhe Hetemi,

Honourable Acting Minister of Education, Science, and Innovation, Ms. Arbërie Nagavci,

Distinguished panelists and participants: Mr. Zef Shala, Chairman of the “Mother Teresa” Association; Mr. Halim Hyseni, former Director of the Pedagogical Institute of Kosovo; Dr. Besnik Bardhi; Ms. Shqipe Gashi; and other former poisoned students and their family members,

Distinguished professors and students,

Ladies and gentlemen,

I am pleased that six months after the first “Zá n’Kujtesë” Forum, which focused on Albanian soldiers killed during their service in the Yugoslav army, we have gathered today for the second forum, which addresses the poisoning of students in Kosovo in the early 1990s.

Whenever we speak of the state violence exercised by Serbia against Albanians under Yugoslavia—of ethnic cleansing and of the crimes committed during the war in Kosovo and prior to it; of apartheid and genocide; of political imprisonments and massive violations of human rights—it is always challenging to orient ourselves within their long history, to understand the origins of this entire trajectory. Perhaps this is because state violence, oppression, discrimination, exploitation and under-representation, and crimes of all kinds—from killings under torture to genocide and massacres—are defining attributes of Kosovo’s history throughout the twentieth century.

Nevertheless, among all these crimes committed by the occupying state of Serbia against us Albanians in Kosovo, one of the most gruesome and diabolical crimes was precisely the poisoning of students. Many of us here experienced that dark time, which remains vivid in my memory even today, as I was a first-year student at the “Xhevdet Doda” Gymnasium here in Prishtina when, in the spring of 1990, it became clear that students were being poisoned in schools.

In fact, the poisoning of students began on 21 March 1989 in Klina and on 6 December 1989 in Prizren. Thus, while preparations were underway for the abrogation of Kosovo’s autonomy—achieved on 23 March 1989—only two days earlier, the first cases of poisoning were recorded at the “Luigj Gurakuqi” school in Klina. At the time, Kosovo had already been under a state of emergency for three weeks. In these extremely difficult circumstances, as Slobodan Milošević was consolidating his rise to power, the authorities of the Yugoslav security institutions and secret services were perpetrating one of the most inhumane crimes in Kosovo.

In the months that followed, beginning on 15 March 1990, cases of poisoning among students were recorded in 20 towns and 11 villages across Kosovo. Beyond students, poisoning cases were also registered among workers at the “Emin Duraku” textile factory in Gjakova, the “Ballkan” factory in Suhareka, the “Polet” factory in Vushtrri, and sporadically among passers-by. There were even reports of seven poisoned children at the “Emin Duraku” nursery in Gjakova.

On 19 March 1990, there were mass poisonings of Albanian students in Podujeva, followed by another wave on 22 March of that year. Tuesday, 20 March 1990, was the peak day of the poisonings, with cases reported in several towns across Kosovo. The largest number of poisoned students would turn out to be in the municipality of Ferizaj, whereas over the years it has been estimated that the total number of poisoned students was 7,421.

The Serbian authorities attempted to camouflage these poisoning cases by obstructing investigations and medical analyses. They also persecuted those who assisted the victims, such as the 48 students of the Faculty of Medicine who were imprisoned for what was described as unauthorized provision of medical aid. Despite these efforts, these state crimes committed by Serbia undoubtedly left behind extensive evidence.

First and foremost, there are the victims themselves—more than 7,421 poisoned students, some of whom have required medical treatment over the years and up to the present day. There are the testimonies of their teachers and professors, their families, and the doctors and medical personnel who provided them with professional assistance; there are various medical reports, such as the report of Dr. Franjo Plavshiq from the “Rebro” Institute in Zagreb; the reports of the Council for the Defense of Human Rights and Freedoms; and the report of the International Commission led by Charles Graves and composed of Verena Graf and Jean-Jacques Kirikijarian, who were later expelled by the Serbian authorities of the time. There are the testimonies of the Catholic nuns in Ferizaj who assisted the victims. There are statements from political leaders of the time, such as the Croatian leader and former President Stipe Mesić, who in 1991 submitted evidence to the Pentagon regarding the involvement of the Yugoslav People’s Army in these poisonings, while it was producing the nerve agent Sarin in a factory near Mostar. There are countless testimonies gathered and published in the press of the time, as well as stories recounted by various witnesses over the years.

In addition to these, there are three serious scholarly works written by Halim Hyseni, Hazir Mehmeti, and most recently Luljeta Pula, in which many testimonies on the history of student poisonings in Kosovo have been collected, analyzed, and presented—some of which are also displayed in the exhibition outside this hall. And it was precisely this aim that guided us four years ago when we began the initial meetings and discussions for the establishment of the Institute for the Research of Crimes Committed During the War in Kosovo. By gathering every material and every piece of evidence on all crimes of any period committed by Serbia against Albanians and others in Kosovo, an archival, library, and audiovisual center is being created within this Institute to serve all researchers, journalists, jurists, and policymakers interested in the historical truth of Kosovo and the policies addressing it.

At the time of the poisonings, our great poet Ali Podrimja wrote the poem “Ndjesë,” (“Apologies”) whose final verse reads:

In this wounding of the soul,

Forgive me, my little one,

If ever I have lied to you

That fascism had gone.

By collecting evidence on the poisonings and on all crimes committed by the Serbian state in Kosovo, by preserving these truths through our state institutions and by cultivating collective memory as a society—by knowing and remembering—we ensure that fascism does not return and that the past does not repeat itself.

Thank you.