New Haven, 30 September, 2024

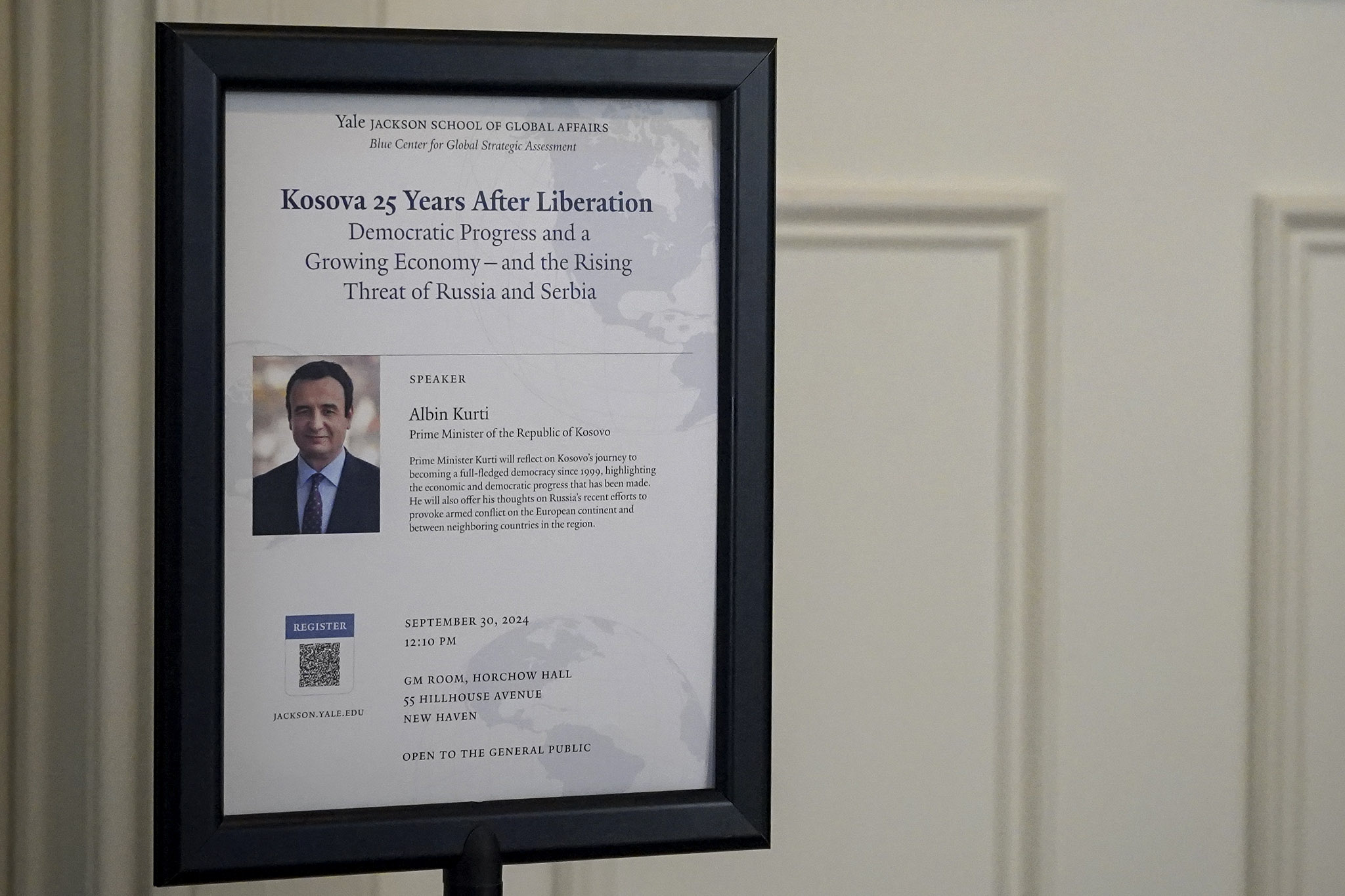

The Prime Minister of the Republic of Kosovo, Albin Kurti, held a lecture and talked with the Executive Director of the “Blue Center for Global Strategic Assessment”, Phil Kaplan, and with students from Yale University, at the Jackson School for Global Affairs, namely on the topic “Kosovo 25 years after liberation: Democratic progress and a growing economy – and the growing threat of Russia and Serbia’.

During his speech, the Prime Minister reflected on the changes our country has experienced and life 25 years after the liberation of the country. He emphasized two perspectives on Kosovo: as a citizen who has analyzed and criticized the government, and the other from someone’s position in the government.

“From both perspectives, I can say that this is a country that values freedom to build a democratic society based on the rule of law,” said the prime minister, adding the importance of history, our main allies and democratic cohesion.

“The growth, especially during the last three and a half years in our government, has been achieved in accordance with democratic values. One of the strongest points of our country is the coherence between our foreign and domestic policies. We are essentially an ally of liberal democracies. This means we join sanctions against Russia, while also investing in renewable energy reforms domestically. This makes our partnership with our allies authentic and shapes every aspect of our government”, said Prime Minister Kurti.

He added that the coherence between values and action, both in domestic and foreign policies, has led to the institutional stability that our country needs, where the liberal democratic order with a social democratic government is what we believe in and what people want most.

Prime Minister Kurti said that the future of our country requires us to be optimistic and vigilant and that Kosovo’s successes are signs of a bright future.

“As we continue with reforms and work towards full integration into NATO and the European Union, our path is clear: to remain steadfast in our values, to work hard, towards innovation and prosperity. And that is why Kosovo is such a successful story. It is a clear example of a simple but powerful message: that democracy can flourish, despite all the challenges, threats and uncertainties. The hope and strength of the people is the biggest and most lasting victory”, Prime Minister Kurti concluded.

Prime Minister Kurti’s complete speech:

Dear students and professors,

It’s a distinct honor and pleasure to deliver the inaugural lecture of Yale’s new Blue Center for Global Strategic Assessment, which aptly examines the interdisciplinary nature of statecraft. As a head of government, whenever you feel honored or humbled, you remember that you represent a country and its entire people. It is never about you personally. So, yes, I accept this honor because I believe Kosova is a prime example of the very topic of discussion—namely, the successful and dramatic evolution from a genocide-surviving people to a functioning democracy and a growing economy in just 25 years.

When asked to reflect, history presents a seeming paradox: some things change significantly, while others remain the same. This lecture reflects on both—the things that remain constant and the ever-changing dynamics of Kosova, or the political life of any country for that matter.

When I visit the US, I am reminded of the rapid technological shifts. Sometimes it feels like we are on the cusp of something transformative, even when we haven’t fully grasped the present reality. Many of you, of course, have been following the discussion of how far generative AI has evolved, how fast its effects are being felt, and what the consequences will be. Opinions on this matter vary greatly. There is a sense of novelty here, a dynamism and capacity for innovation, that I’ve noticed is less pronounced on the other side of the Atlantic.

And yet, certain things remain unchanged, though they may take different forms. The uncertainty surrounding upcoming elections is constant—in what has been dubbed the year of elections. We are in a continual state of analyzing which aspects of a campaign could prove detrimental to the final outcome in November. And, of course, topics taking center stage in this election—gender, economic, and other forms of inequality—do persist. Even in 2024, amidst all the unprecedented change, some things remain evergreen, such as the central question: How to strengthen democracy? And in times of crisis, how do we save it?

The same paradox—this coexistence of change and continuity—is also present in the political and general life of Kosova. While we in Europe may not be at the forefront of technological breakthrough to the same extent, the country has nonetheless been transformed. If you’ve seen Kosova over the last 25 years, you might not recognize it today. This year, as we hosted many foreign leaders during our celebrations, they couldn’t either. I would argue that we have made monumental political transformations.

Mr. Kaplan’s introduction takes me back to my student days. The protests in the 1980s in Kosova were an inflection point—the canary in the coal mine. By the end of the ’80s, the autonomy Kosova had enjoyed since 1974 was revoked, leading Slovenia to call for recognition of human and civil rights in Kosova. As violations worsened, the calls echoed across Europe and the West. And when I joined the protests in the late ’90s—which meant being brutally beaten by Serbian police—it was the last call to stop the violence before it escalated. A few months later, war erupted, resulting in genocide and other crimes that the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia later termed “crimes against humanity.”

Now, the country is led by a government that is freely elected, where protests are encouraged, and where the police work for the people. This is evidenced by the latest Gallup Poll, which ranks Kosova among the top 10 countries worldwide for the Law and Order Index Score, placing us among nations like Norway and Switzerland. It is a country where education is encouraged, public universities are now free of charge for bachelor’s and master’s students, and where 50% of the STEM, science, technology, engineering and math student body are women. International organizations recognize us as an “electoral democracy.”

Change triggers further imagination, brings uncertainty, and enhances fear. In times of uncertainty, we must ground ourselves in what remains constant, independent of circumstances or location. For us, that constant is our origin story—what we were fighting for.

A country must define what it stands for; it cannot solely define itself by what it opposes. Every people has an origin story that follows it throughout history. For us, liberation is that story, and it influences us profoundly. The origin story of the US, rooted nearly two and a half centuries ago, still influences the dynamism and value of freedom in this country. Our story is still within our living memory. Its influence is profound and actual.

I have two perspectives on Kosova. I refer to the country’s name in Albanian, which I believe is more authentic for me, as a native speaker of Albanian. One perspective is as an outsider, a citizen who has analyzed and critiqued the government. The other one is from the position of someone in power. From both perspectives, I can say that this is a country that values the freedom to build a democratic society based on the rule of law.

Our origin story contains many of the multitudes that helped shape the country and continue to inform our vision. Our story is one of seeking the recognition of human rights. It is a story of having our plight acknowledged by our allies—especially large powers such as the US, the UK, Germany, Italy, and France—of democratic cohesion, and of honoring the efforts of many by creating strong and transparent institutions that, at their core, serve human rights and an ideal of free and equal citizenship.

Our population skews young, with an average age of 34. With that youth, we had to embrace a vision, because the immediate aftermath of the war was marked by great devastation and persisting uncertainty—even the country’s status was unresolved. In 2000, our GDP was merely $1.8 billion. This year, for the first time in our history, our GDP reached double digits.

But the growth, especially over the past three and a half years under my government, has been achieved in alignment with democratic values. One of our country’s greatest strengths is the coherence between our foreign and domestic policy. We are fundamentally an ally of liberal democracies. This means we join in sanctions against Russia while also investing in clean energy reforms domestically. I have seen cases where governments are democratic in foreign policy but less so in their domestic policies, and that cracks sooner than later.

This makes our partnership with our allies authentic and informs every aspect of our governance.

Returning to the analogy of change versus continuity, there is something that is unchanged, a major question about security in Europe, and naturally, the Western Balkans as well. The war in Ukraine is the first European war in over a hundred years, that the Western Balkans have not participated in. But that doesn’t mean we are unaffected.

We are especially vulnerable to Russian aggression because Serbia maintains close ties with Russia. The ties are not merely historical or religious; the two countries are deeply intertwined in their economies and ideology—Russia has a majority stake in Serbian energy companies, for example and Russian investments in Serbia have increased eightfold since the invasion of Ukraine. But the influence extends far beyond the fields of energy and intelligence, reaching universities, media, and the broader cultural and intellectual spheres. Serbia is the only European country – other than Belarus – to refuse to impose sanctions on Moscow for the war in Ukraine. It has also never voiced any opposition for any other war that Russia has waged including the war in Georgia and 2014 invasion of Ukraine. This alliance has also invited the presence of China, which is Serbia’s primary trading partner outside the EU. There is a sense that the depth and breadth of ties between Russia and Serbia, and consequently Russia’s direct influence in the region, have been underestimated by Western political figures.

For us, the threat is not theoretical. Almost exactly a year ago, around 100 Serbian paramilitary troops entered our country and opened fire on our police, killing one sergeant. Despite the technological developments and extensive information available to identify the perpetrators, there is no accountability from Serbia. The Serbian and Russian threat also persistently endangers other countries in the region. For example, Russia unsuccessfully attempted to buy the Port of Tivat in Montenegro in 2015. The following year, it orchestrated a coup against then-Prime Minister Milo Đukanović.

We are keenly aware of the region we operate in. We aim to be guided by democratic values while tailoring them to our context, shaping our military, economic, social, and political structures. Militarily, we focus on ensuring the safety of our citizens and their freedom from threats. This focus has driven our increased defense spending, and we have benefited greatly from the NATO presence, which has helped us build and strengthen the Kosova Security Force. For instance, we have surpassed 2% of GDP spending on our military.

This coherence between values and action—both domestically and in foreign affairs—has led to the institutional stability our country has needed. Liberal democratic order with a social democratic government, is what we believe in and people want most.

Our government will face elections next year. It will be the first time in the post-independence period that we will have completed a full four-year term in office. Our government has achieved many firsts. It is the first time we have made public higher education free in our country. It is the first time publicly-owned companies have begun operating at a profit or break-even point. It is also the first time our institutional services have extended to the northern part of the country, which had previously become a quasi-lawless zone rampant with crime. It is the first time we have given universal subsidies to new mothers and to children below the age of sixteen, and the first time we have given incentives to the private sector to stimulate the hiring of youth, women, and individuals who come from families who are unemployed. Kosova citizens have now visa-free travel to the European Schengen zone which covers the EU. And we have just concluded negotiations for a free trade agreement with EFTA which consists of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This is the second time in the past week that a poll or event has brought us closer to Norway and Switzerland – which is exactly the desired outcome.

We have earned the trust of our people, as evidenced by a 2/3 increase tax revenue during our mandate, without changes in fiscal policy—an indication of people’s confidence in the government’s strategy for managing and allocating resources.

In these times, where facts are increasingly questioned, this trust matters greatly. 2016 was a pivotal year on both sides of the Atlantic, with the US elections and the Brexit vote. Since then, the shifts have become more pronounced, and in such times, urgency and agility matter more than ever.

Democratic backsliding is a global concern. According to Freedom House’s February Report of 2024 in the World analysis, the world has experienced nearly two decades of democratic decline. This has been worsened by the rise of authoritarian powers like China and Russia, conflicts such as the war in Ukraine, and the spread of right-wing extremism—even in countries that were once seen as safeguards of democracy.

For my country Kosova, this means stronger alliances with democratic allies. It also means urgency in joining NATO and the EU, likely in that order. This urgency also implies a commitment to necessary reforms. And all geopolitical voids left – in the Western Balkans and beyond – will be weaponized. In the current landscape, no empty space is neutral space.

There is a strong need for democracies—both existing and emerging—to stand firmly together. This requires us to view authoritarian threats with caution and accept the limitations of bridge-building. If you have followed Western Balkans politics, you will have heard both the government and analysts express skepticism about appeasement—be it towards Belgrade or Moscow.

I understand the desire for bringing different, and ideologically opposing, parties together—if successful, it is a far better alternative to conflict. But we have also seen the limits of economic interdependence in securing peace.

The war in Ukraine has already cost Russia over 70,000 troops and another 400,000 wounded soldiers. This shows that some countries are willing to sacrifice their own people to invade another nation. Its commitment to violence is well documented. Since 1817, Russia has been involved in 48 wars, with an average interval of 4.4 years between them, from the beginning of one to the beginning of the other. Europe has long coexisted with an imperialist Russia, but the current geopolitical landscape and human rights protections make such coexistence increasingly difficult. As their power wanes and becomes a far cry from the heights of their imperialism, their danger increases as they forcefully seek to regain influence. The way we respond to such aggression will not only shape our relationship with Russia but also with all other authoritarian powers. The actions of authoritarian powers and the responses of democracies are closely watched by other nations gauging their own limits in these situations. And this question before us, requires a telling answer.

The story of Kosova is manifold. But overwhelmingly, it is a story of success—the success that came from fighting for human rights and later creating institutions that uphold these rights. It is also a story of perseverance in transforming and trusting that political major changes can happen when the right to vote is exercised. It is a story of the importance of alliances. Just as people mirror each other through interactions, so do countries. Our alliances from the start have served as important models in how we shape our governance and our future. For example, the Council of Europe—the foremost human rights body on the continent—has lauded Kosova as having one of the strongest constitutional protections for human and minority rights across Europe. It is also a story of grounding oneself in core truths during a changing landscape—truths that have inspired our tireless fight to become the youngest country in Europe after declaring independence in 2008, and remain our north star as we move forward.

The future of our country asks us to be both optimistic and vigilant. The successes of Kosova—becoming the leading Western Balkans democracy and experiencing an average of over 6% economic growth in the past year—are signs of a bright future. As we continue to reform and work toward full integration into NATO and the European Union, our path is clear: standing firm in our values, working hard, innovating, and prospering.

And that is why Kosova is such a success story. It is a stark example of a simple but powerful message: that democracy can thrive, despite all the challenges, threats, and uncertainties. The hope and strength of the people is the biggest and most lasting victory.

Thank you.